Baudelaire: A Doubter Without Love

Aged just twenty-five at the time of publication, Baudelaire is confident, endlessly quotable, but resolutely indecisive. He is a flaneur of opinion. Recently re-released by David Zwirner Books, The Salon of 1846 is a review of the annual exhibition held at Louvre palace. Baudelaire searches for certainty in criticism and painting, he values consistency in style, clarity of vision, feeling. The book is divided into a series of essays. In the first, “What is the Good of Criticism”, Baudelaire exclaims, “criticism should be partial, passionate and political, written from an exclusive point of view”. He deplores the “eclectic” painter, “a doubter”, “a man without love”, “neither star nor compass”. Guignet “carries two men about in his head”. Gigoux’s painting “looks like a work by one of those countless masters of the Florentine decadence”. Brune: “no soul – no great faults, but no great quality.” Cabat, “deserted the path on which he had won himself such a great reputation.” Yet Baudelaire is guilty of his own criticism: he is “a ship which tries to sail before all four winds".

Vernet’s studio-barracks: The Artist's Studio, Horace Vernet, c.1820

“Partiality” is something like a contronym, a word with contradictory meanings, perhaps a “Janus word”, i.e. Janus-faced, i.e. two-faced. To be partial means to support, show bias towards a particular argument or belief, demonstrate an unshakeable commitment to a cause but it also means to have a liking or taste for something, often culinary, more of a casual attachment, given to change, easily influenced, dependent on circumstance, mood, time of day, an appetite which is forgotten once satisfied. Baudelaire is critic of partiality, caught in the middle of the road, between anarchist and flaneur. He tell us “impartiality” is the “impotence of the eclectics”. In life and art, the more restricted someone’s field of vision, the more intense their focus. “Grasp all, lose all,” he instructs the reader. The partial painter is a fierce revolutionary, never deliberates. “The first business of an artist is to protest”. For Baudelaire, a work of art is a kind of insurrection, “spontaneous and urgent”. At the same time, the critic is a flaneur, a favourite character in Baudelaire’s writing. The flaneur is a lover of life who sees the world anew each day, a bon vivant, a connoisseur of exquisite taste in painting and gastronomy. “Only the flâneurs appreciate” Tassaert – his orientalist Marchand d’esclaves gives Baudelaire hope for more “ravishing things” to come in the future. On the varying quality of the year’s exhibition: “A fine dinner contains both hors d’oeuvres and main courses.” Andon Decamps’ painting: “the most appetizing dishes” have “less relish and tang”.

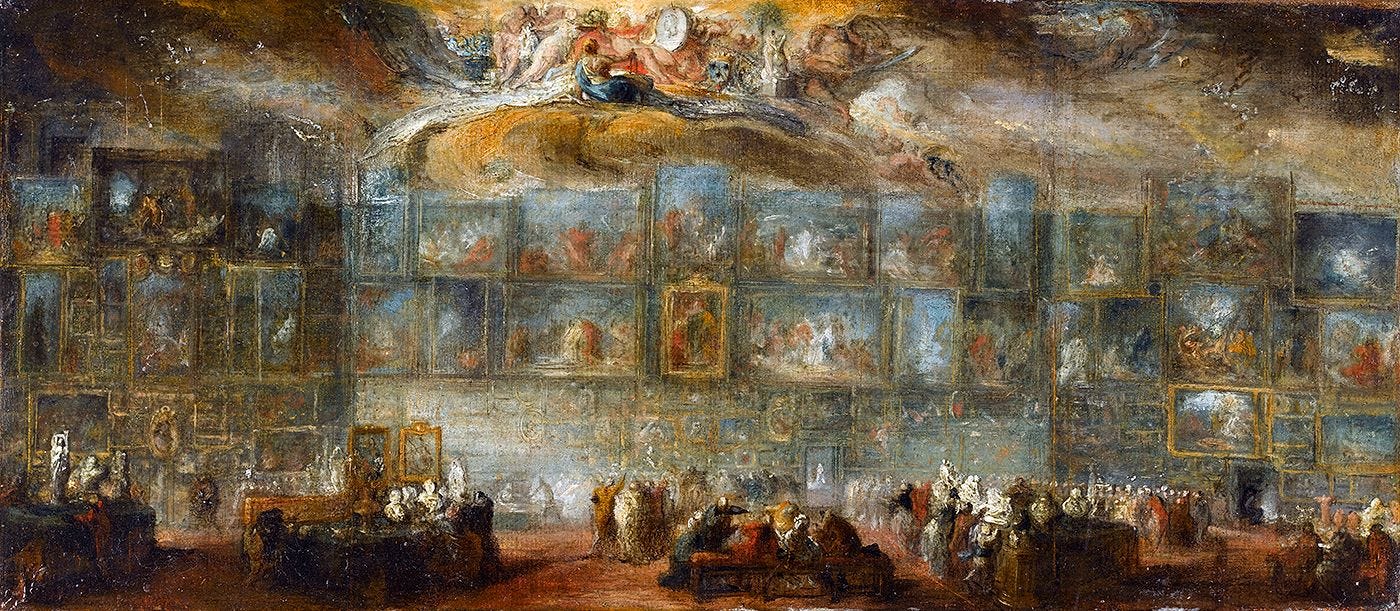

All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Salon of 1779, Gabriel de Saint Aubin

Baudelaire samples different paintings and politics as if offered up on a silver platter. He fought with the revolution in February and June 1848, and again against Napoleon’s coup in December 1851, but calls republicans the “suffering minority”, the “enemy of art”. “I hate the army, the police force” and their “noisy arms”, he declares. He is disgusted by Vernet’s military propaganda, a jackboot thug who paints “to the sound of pistol shots”. In his 1859-60 essay “The Painter of Modern Life” however, Baudelaire celebrates the image of the regiment, “marching like a single animal, a proud image of joy in obedience!” Again, in The Salon of 1846, the author delights in the thought of a municipal guard thumping a republican: “He wants to be free, poor fool. […] Thump him devoutly across the shoulder blades, the anarchist!”. Likewise, he calls on critics to "pitilessly thump” amateur artists, “emancipated journeymen”, who lack respect for the established “schools of painting”, the “sovereignty of genius”. “Today no one is obedient,” he groans. “Everyone wants to rule”, a “little place of one’s own”. Baudelaire tries to bend the world to his will. He champions conformity, law and order, rather than artistic joy and freedom of expression.

As Marshall Berman argues in All That Is Solid Melts into Air (1982), Baudelaire switches between hope and despair, from “modernism without tears”, a “pastoral” vision of modernity, to disenchantment, apostasy and self-pity. "My halo slipped off my head and fell into the mire of the macadam," sulking in his 1865 prose poem The Loss of a Halo. Baudelaire can't face the disappointment of the world but never dares, won't commit to the dangerous possibility his writing might also be a source of hope for others. Critics should be principled and political, committed not necessarily partial, still loud but steadfast, guided by their own moral compass not the ages' changing winds.